Dr. Gabrielle_PhD

Associate Professor, Head of Behavioral Sciences Department

University of Medicine and Pharmacy “Carol Davila”

Introduction

Neurofeedback (NF) is EEG-based brain training: we measure brain activity in real time and provide audio-visual feedback so that the brain gradually learns self-regulation (focus, calm, flexibility). The natural question is: “Isn’t it actually placebo?” When we see effects in animals (cats, horses) and measurable results in athletes, a placebo-only explanation becomes unconvincing.

1) What is Neurofeedback (NF)?

Linear (protocol-based) NF

Targets are set for specific EEG bands (e.g., ↑SMR 12–15 Hz for motor stability/calm; ↓theta for vigilance). The system “rewards” activity when it enters the desired zone (sounds/images). Think of it as a fixed gym program.

Non-linear (dynamic/adaptive) NF

It does not push one band; it mirrors micro-variations in brain activity and flags deviations, letting the brain find balance by itself—more like smart sparring, where body/brain naturally adjust their response.

Important: The goal of NF isn’t a “miraculous cure,” but training control over internal states (attention, reactivity, emotions)—just as physical training builds endurance.

2) “No two cases are alike” — why we personalize

Each brain has a unique fingerprint (genetics, life history, neural networks). What works for one person with the same diagnosis isn’t guaranteed for another.

The key to personalization is Brain Mapping (QEEG): the quantitative EEG map highlights areas of hyper/hypo-activation and guides the individual protocol—exactly like personalized training plans in elite sport.

3) Animals & neuroscience: horses and cats

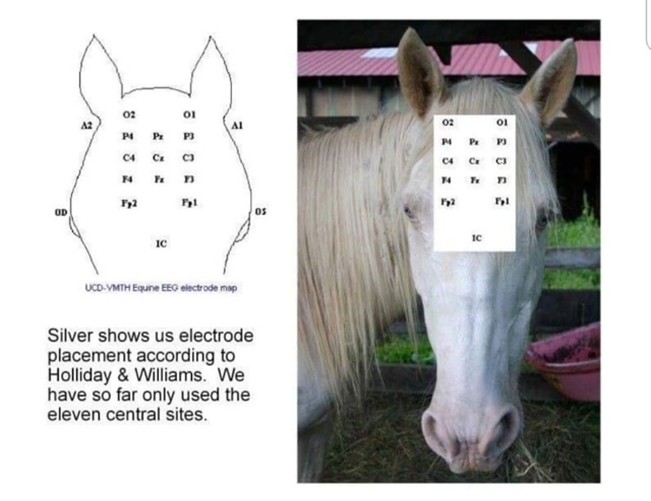

3.1. Where do we place electrodes on a horse’s head?

Researchers adapt the human 10–20 system to the horse’s head (frontal, central, parietal, occipital—left/right). Veterinary studies describe non-invasive electrode placement and EEG markers across sleep/wake states.

3.2. “Cavallo rinato con le neuroscienze”: Davidson du Pont

The trotter Davidson du Pont won the Prix d’Amérique Legend Race on January 30, 2022—a widely reported comeback in one of harness racing’s most demanding environments. While news stories cited stress-regulation approaches around the horse’s care and training, the important point here is that animal performance changes cannot be attributed to conscious expectation, unlike classic placebo effects.

Why does this matter?

With animals, we can’t invoke the conscious expectation central to placebo. When performance improves alongside neurophysiological regulation, we gain an objective argument.

4) Barry Sterman’s cats — the modern beginning of NF

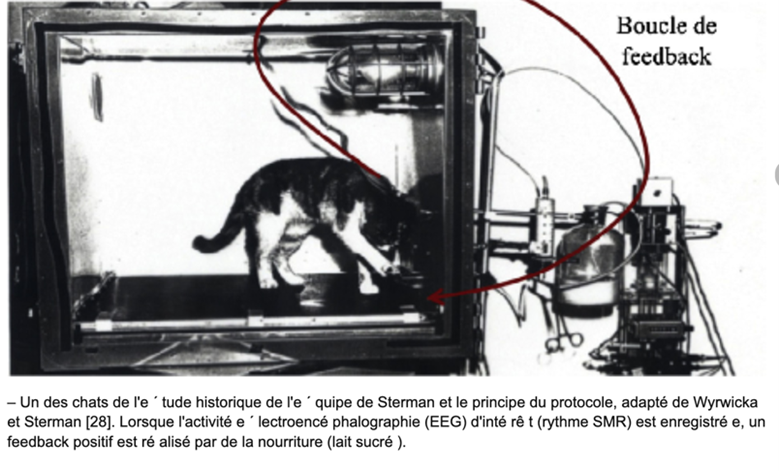

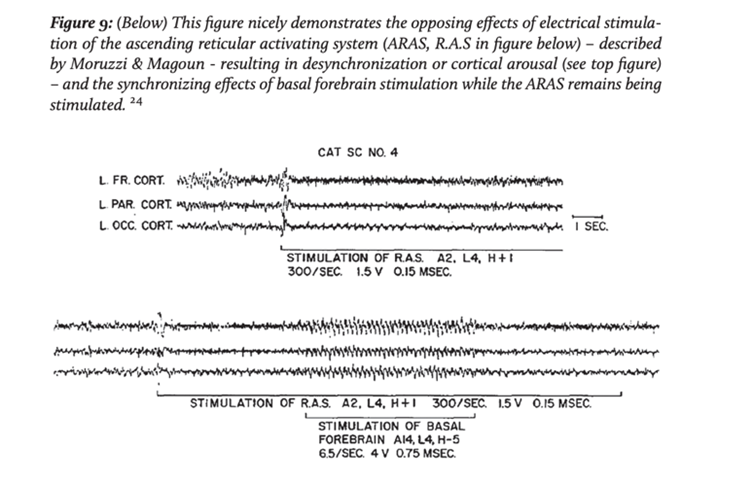

At UCLA/NASA, Barry M. Sterman trained cats to produce the SMR rhythm (≈12–15 Hz). Later, the same animals exposed to monomethylhydrazine (a convulsant rocket fuel) showed greater resistance to seizures versus controls—evidence of training-induced neuroplasticity, not mere suggestion. (See Brain Research 1972; Aerospace Medicine 1969; overview in Clinical EEG 2000.)

5) Athletes & performance: what studies show

Converging research indicates that NF can improve motor performance, reaction speed, attention, and emotional self-regulation, including in precision sports (shooting, archery, golf). Recent systematic reviews/meta-analyses in sport contexts report performance benefits while also calling for rigorous RCTs and adequate sample sizes.

6) “But what if it’s placebo?”

Placebo is not “nothing”; it’s a real neurobiological response (e.g., dopaminergic and endogenous opioid pathways) driven by expectation and learning. Yet animal data cannot be explained by conscious expectation, and sham-controlled human studies often show differences between real NF and sham conditions.

7) The parallel with physical training

Could you run a marathon without training? Maybe—but at huge cost. Likewise, mental training is built through small, consistent, personalized steps (QEEG-guided)—without miracle promises, but with cumulative gains in attention, self-regulation, and performance.

Conclusion:

Neurofeedback is neither magic nor a one-size-fits-all solution. It is personalized mental training, guided by QEEG, which—over time—can enhance focus, emotional resilience, and performance. The fact that we observe effects in animals and measurable results in athletes points to real neurophysiological mechanisms, not just placebo.

References:

Aleman, M., Williams, D. C., & Holliday, T. A. (2008). Qualitative and quantitative characteristics of the electroencephalogram in normal horses during spontaneous drowsiness and sleep. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 22(3), 630–638. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18466241/

Benedetti, F., Mayberg, H. S., Wager, T. D., Stohler, C. S., & Zubieta, J.-K. (2005). Neurobiological mechanisms of the placebo effect. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(45), 10390–10402. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3458-05.2005

Cheng, M.-Y., & Hung, T.-M. (2024). Evaluating EEG neurofeedback in sport psychology. Frontiers in Psychology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1331997/full

Onagawa, T., et al. (2023). Meta-analysis of EEG neurofeedback on motor performance in healthy adults. NeuroImage. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1053811923001465

Prix d’Amérique Races. (2022, January 30). Prix d’Amérique Legend Race: Davidson du Pont finally awarded. https://www.prixdameriqueraces.com/en/news/race/prix-damerique-legend-race-davidson-du-pont-finally-awarded/

Rydzik, Ł., et al. (2023). The use of neurofeedback in sports training: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10136619/

Standardbred Canada. (2022, January 30). Davidson Du Pont Wins Prix d’Amérique. https://standardbredcanada.ca/news/1-30-22/davidson-du-pont-wins-prix-damerique.html

Sterman, M. B. (1972). Cerebral and behavioral studies of sensorimotor EEG biofeedback in the cat. Brain Research, 38(2), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(72)90147-2

Sterman, M. B., LoPresti, R. W., & Fairchild, M. D. (1969). Electroencephalographic and behavioral studies of monomethylhydrazine toxicity in the cat. Aerospace Medicine, 40(6), 608–613. (PDF UCLA) https://teams.semel.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/publications/78_monomethylhydrazine_seizures_bowersox_siegel_sterman.pdf

Sterman, M. B. (2000). Basic concepts and clinical findings in the treatment of seizure disorders with EEG operant conditioning. Clinical EEG and Neuroscience, 31(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/155005940003100111

Tosti, B., Corrado, S., et al. (2024). Neurofeedback training protocols in sports: Recent advances in performance, anxiety, and emotional regulation. Brain Sciences, 14(10), 1036. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3425/14/10/1036

U.S. Trotting Association News. (2022, January 30). Davidson du Pont wins 101st Prix d’Amérique. https://ustrottingnews.com/davidson-du-pont-wins-101st-prix-damerique/

Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A., et al. (2013). Principe du biofeedback [Figure]. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Principe-du-biofeedback-adapte-de-Micoulaud

Image sources: 1) Micoulaud-Franchi, J.-A., et al. (2013), Principe du biofeedback — translated image (ResearchGate). 2) UC Davis VMTH – Equine Sleep & Sleep Disorders (overview) and Aleman et al., 2008 (JVIM) for equine EEG landmarks., 3-6). Davidson du Pont — images from official and media sources: Prix d’Amérique (official), U.S. Trotting Association News, Standardbred Canada; see the articles in the bibliography. Some images are included in the articles in the attached bibliography.

From research to practice: the official UCD-VMTH equine EEG electrode map (Holliday & Williams) applied in neuro-functional assessment.

A major step towards integrating neuroscience into equine performance. 🧠🐎

#neurowellness #neuroscience #EEG #equineperformance #neurofeedback #neuromirror #mentaltraning